The Story of Temple Drake (1933) Starring: Miriam Hopkins, William Gargan, Jack La Rue, Florence Eldridge, Sir Guy Standing Directed by Stephen Roberts. Screenplay by Oliver H. P. Garrett. Based on the novel Sanctuary by William Faulkner (New York, 1931). Produced by Emanuel Cohen. Run time: 72 minutes. US. Black and White. Drama

It’s easy to get the impression that Pre-Code

Hollywood films were full of nudity, sex, drugs, murder and gambling, but in reality,

for the most part, they dealt with very similar topics to those made from 1934

to 1968 when the Production Code was in force. Every film made and released

between 1930 and 1934 is technically Pre-Code, though that moniker is usually

reserved for films like The Story of Temple Drake (1933), meaning that its subject matter

would not be dealt with at all or not dealt with in the same way after 1934.

The Code, which was Hollywood’s attempt at

self-censorship, grew out of what were seen by some as excesses on the screen,

in dealing with topics like sex and violence, as well as off the screen

scandals that popped up in the film community. Perhaps the two best known are

the murder of film director William Desmond Taylor and the charges of rape

leveled, but never proven, at Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle in the death of actress

Virginia Rappe.

Just as Major League Baseball had set up the

office of Commissioner to right its image following the Black Sox scandal in

1919, Hollywood turned to Will Hays, former Postmaster General, to guide it.

With pressure from state censorship boards and the Catholic Legion of Decency,

Hollywood adopted a code by which the studios agreed to subjects and situations

their films would and would not deal with.

Hays was brought in to head the Motion

Picture Producers and Distributors of America, the precursor to today’s MPAA, in March 1922. He spent the majority of his time trying to convince state

censorship boards not to ban or censor Hollywood movies. At that time, the

states required the studios to pay the censor boards for each foot of film

excised and for each title card edited. Add to that, studios also had the

expense of duplicating and distributing separate versions of each censored film

for the state or states that adhered to a particular board's decisions.

The original code, or what Hays called

"The Don'ts and Be Carefuls," was written to reduce the likelihood

cuts would be required, since each board kept their standards a secret. Hays’ set of guidelines did reduce the calls

for the Federal government to get involved.

The Production Code was actually written in

1929 by Catholic bishops and lay people, including Joseph Breen, and presented

to Hays, who was enthusiastic about it. However, the studio heads were not.

From 1930 to 1934, they worked under the Code, but largely ignored it, that is

until Breen was brought in as its enforcer. Films like The Story of Temple

Drake led to the code's enforcement.

The novel the film is based on, Sanctuary,

was one of the first novels that established William Faulkner as a great

American novelist. Controversial because it dealt with the subject of rape, it

was considered his commercial and critical breakthrough as an author.

Making a movie about such a book was not without controversy. George Raft, an actor who turned down more parts than anyone I’ve heard of, refused to play the role of Trigger (Popeye in the novel). Paramount suspended him for his refusal.

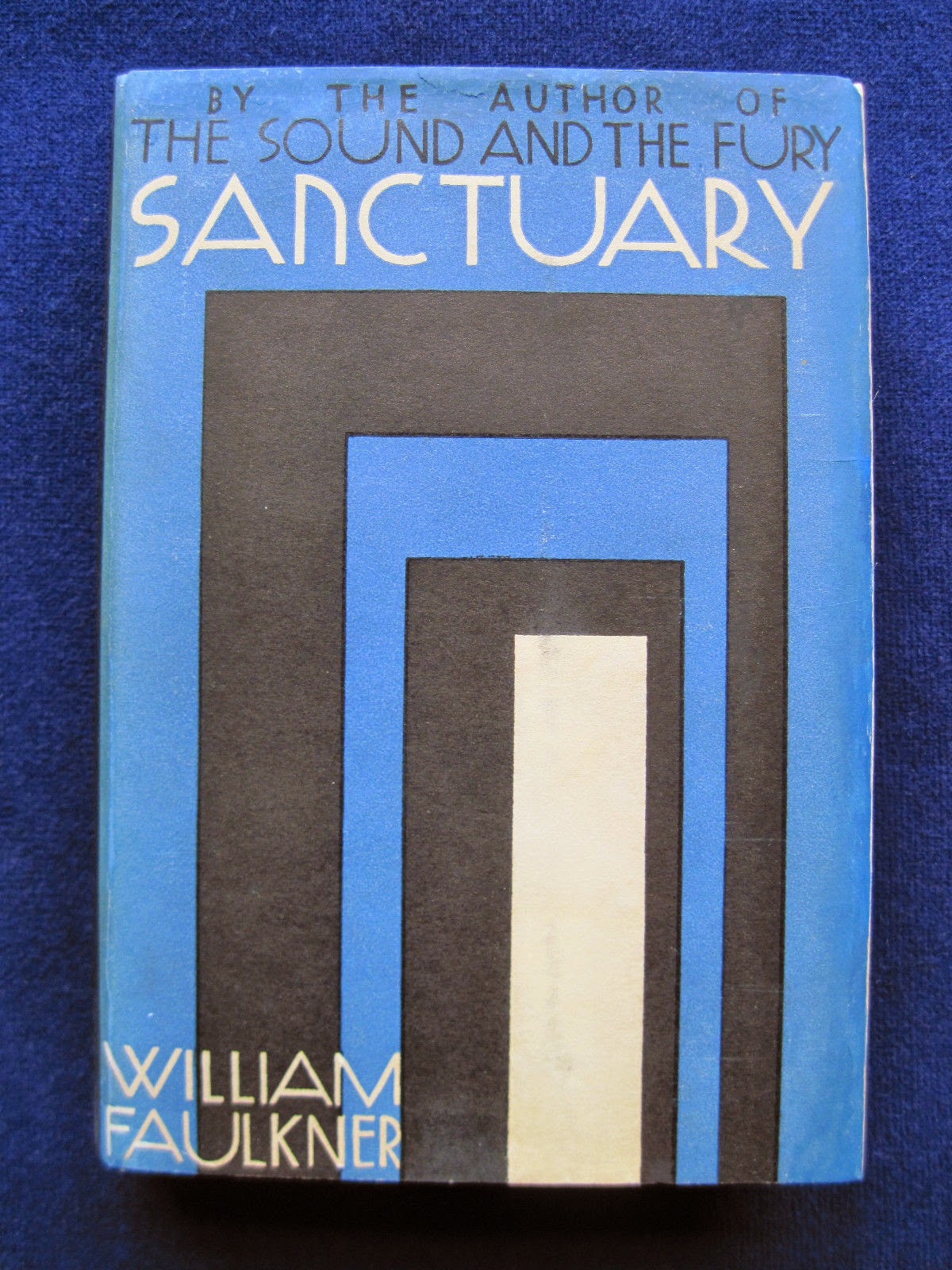

|

| Sanctuary by William Faulkner. A book the Hays Office didn't think should be made into a movie. |

Making a movie about such a book was not without controversy. George Raft, an actor who turned down more parts than anyone I’ve heard of, refused to play the role of Trigger (Popeye in the novel). Paramount suspended him for his refusal.

And of course, the Hays Office had its

problems with making such a novel into a movie. Joseph I. Breen, who was in charge of

public relations for the Hays Office, admitted in a memo dated March 17, 1933

that he had not read the novel but was convinced that people would say that the

filmmakers had adapted for the screen "the vilest book of the present years."

Any reference to the book was forbade in advertising for the movie.

After a preview

screening, the Hays Office gave a list to Paramount of cuts it wanted made, but

more about those later.

In the film, Temple

Drake (Miriam Hopkins) is the granddaughter of Judge Drake (Sir Guy Standing)

in the Southern city of Dixon. No exact location is ever given, but the novel

takes place in Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi.

|

| Temple Drake (Miriam Hopkins) comes home late and runs into her grandfather, Judge Drake (Sir Guy Standing). |

Temple is a wild child who teases men, but does not sleep with them. Despite that, reputable lawyer Stephen Benbow (William Gargan) is in love with her and asks her to marry him. But Temple thinks Stephen is too serious and turns him down.

She would rather

cavort with other suitors, including Toddy Gown (William Collier, Jr.), who’s

preoccupation with Temple is only surpassed by his love of drink. When Temple

and Toddy arrive at a party, she ends up dancing with Stephen, who gets too

serious on her again. In order to escape, she asks Toddy to take her someplace

and he has liquor on his breath and on his mind.

|

| Toddy Gown (William Collier, Jr.) thinks he's on top of the world. |

Speeding through the country roads, it isn’t long before Toddy crashes the car. In these pre-seatbelt/air bag days, the couple is thrown from the car, but except for a cut on his head, they both don’t seem worse for wear. A tough bootlegger named Trigger (Jack La Rue) and his simple-minded sidekick, Tommy (James Eagles), are the first to find them and Trigger tells Tommy to take them back to a nearby speakeasy run by Lee Goodwin (Irving Pichel), which is in a dilapidated southern mansion.

|

| Tommy (James Eagles) leads Temple and Toddy to a speakeasy after their accident. |

Temple doesn’t want to go, but she has no choice. A thunderstorm is brewing. When they get to the house, she doesn’t want to go in; the room is full of men, which now includes Toddy, who are sitting around getting drunker by the minute. But it starts to rain and she eventually comes in through the kitchen, hoping the woman of the house, Ruby Lemarr (Florence Eldridge), will be more sympathetic to her plight. She isn’t.

|

| Unhappy with her predicament, Temple turns to Ruby (Florence Eldridge) for sympathy, but her pleas fall on deaf ears. |

Temple, being

the only single woman in a room of men, is manhandled. When Toddy tries to

defend her honor, he is knocked out unconscious, leaving Lee to defend her.

Ruby takes some pity on Temple, who is in over her head, and takes her upstairs

to one of the bedrooms where she can get out of her wet clothes.

The men have to

make a pre-dawn delivery to the city, but still have time to try and put the

moves on Temple. It takes shotgun wielding Tommy to keep them at bay. Trigger

insists on taking Toddy with them, but is as insistent that Temple stay there.

Feeling that she

might be safer out in the barn, Ruby moves her in the night. Even with Tommy

sitting by the door, shotgun across his lap, she has a hard time getting to

sleep. The next morning and the men are back from their delivery in the city

and Temple is still out in the barn.

Trigger returns

and, sneaking through the haylofts, gets around Tommy’s protection. However,

Tommy hears him and does check on what’s going on. Trigger shoots him for his

troubles and then rapes Temple.

But the torment doesn’t stop there. Trigger takes Temple with him to the big city to Miss Reba’s (Jobyna Howland) place, a brothel where he has a room. He tells Temple she’s free to leave, but he doesn’t let her. The time Trigger and Temple are at Miss Reba’s is left vague. It could have been a matter of days or it could have been weeks. We’re spared the details, but they are there quite a while as she gets new clothes and doesn’t try to escape, no doubt feeling that her reputation was ruined forever and she couldn’t go home.

|

| The rape of Temple by Trigger (Jack La Rue) as shown in the film. |

But the torment doesn’t stop there. Trigger takes Temple with him to the big city to Miss Reba’s (Jobyna Howland) place, a brothel where he has a room. He tells Temple she’s free to leave, but he doesn’t let her. The time Trigger and Temple are at Miss Reba’s is left vague. It could have been a matter of days or it could have been weeks. We’re spared the details, but they are there quite a while as she gets new clothes and doesn’t try to escape, no doubt feeling that her reputation was ruined forever and she couldn’t go home.

|

| You can argue Temple goes away with Trigger willingly, but when given a chance to attempt an escape, she does nothing. |

Judge Drake, who doesn’t know Temple’s true nature, plants a story in the press that she’s visiting relatives in Pennsylvania. Toddy, who wakes up in a Dixon warehouse the morning following the storm, skips town.

And they might

have stayed hidden from sight, except for the murder of Tommy. Lee is charged

with the crime and Stephen is assigned to defend him. But Lee is afraid of

Trigger and won’t talk. He is doomed to be convicted, but Ruby offers that

Trigger and some girl were there that night. She suggests Trigger might be at

Miss Reba’s and Stephen, armed with a subpoena, goes looking for Trigger.

He bluffs his

way into the house and enters Trigger’s room where he is shocked to find

Temple. Stephen is prepared to fight for her honor, but unbeknownst to him, Trigger

has a gun on him. Seeing Trigger going for his revolver, Temple intercedes. She

tells Stephen that she is there on her own will and is in love with Trigger.

Stephen doesn’t like what he hears, but he leaves.

Trigger is fooled by Temple’s play and is surprised when she is preparing to leave him. But Trigger isn’t done with Temple and throws her down on the bed. Unfortunately for him, it’s right on top of his gun. Temple shoots and kills Trigger. Temple manages to avoid detection and sneaks out of Miss Reba’s, hails a cab and is driven the 100 plus miles back to her hometown of Dixon.

|

| Temple does her best to convince Stephen (William Gargan) that she's happy in her life with Trigger. |

Trigger is fooled by Temple’s play and is surprised when she is preparing to leave him. But Trigger isn’t done with Temple and throws her down on the bed. Unfortunately for him, it’s right on top of his gun. Temple shoots and kills Trigger. Temple manages to avoid detection and sneaks out of Miss Reba’s, hails a cab and is driven the 100 plus miles back to her hometown of Dixon.

Meanwhile,

Stephen is trying to defend Lee, who still refuses to speak on his own defense.

During a brief recess, Stephen is confronted by Judge Drake, who doesn’t want Temple

to have to testify. Temple tries to convince Stephen not to call her by telling

him what she’ll have to confess to in the trial, including the murder of

Trigger. But Stephen feels compelled by his duties to call her.

But when she’s

in the witness stand, his love for her prevents him from questioning her,

knowing that it will lead to ruin, and dismisses her as a witness. Suddenly

Temple, knowing right and wrong, confesses about all that has happened to her,

including being witness to Tommy's murder, being raped by Trigger and finally

her killing Trigger to get away.

After she’s said everything, she faints. Stephen picks her up and carries her out of the courtroom, telling Judge Drake that he should be proud of her because he is.

|

| Stephen can't bring himself to question Temple when she appears on the witness stand. |

After she’s said everything, she faints. Stephen picks her up and carries her out of the courtroom, telling Judge Drake that he should be proud of her because he is.

The Hays Office

had already pronounced their concerns about making Sanctuary into a movie and

even things in the film that hinted at some of the action in the novel had to

be changed after Previews. In the book, Popeye, the rapist, uses a corncob to

violate Temple. In the original version, there were shots in which a corncob

was picked up and looked at following the rape scene. The location of the rape

was moved from a corn crib to the barn and no mention of corncobs or references

to corncobs or corn cribs were allowed.

A shot of the hat

rack at Miss Reba’s filled with men’s hats was also cut from the film, in an

effort to keep it from too obviously being a house of prostitution. Also cut

was Miss Reba’s line “I got some of the biggest people in town right here in

this house spending their money like water” and "Just got back from church

myself." Reba’s use of the word

chippie (slang of the day for a young woman of low moral character) was

covered up with a clap of thunder.

Likewise a line

of Ruby’s that she could pay "Lee's" lawyer with sexual favors was

also cut from the final film.

There was even

some disagreement about handling Temple’s testimony on the witness stand. The

matter of how long she was at Miss Reba’s had to be dealt with somehow.

Originally, in her confession she states "No, I wasn't a prisoner"

was excised. Instead, when she admits she stayed at Miss Reba's place, the

judge interjects, "a prisoner, you mean," and her response is an

ambiguous stare.

An epilogue showing Temple doing welfare work in China was

suggested, but the Hays Office rejected the idea, insisting she not be shown

working as a missionary and feeling it is obvious she is not a fugitive from

justice.

The success of

the film depends on the performance of Miriam Hopkins. While I’m not all that

familiar with her work, she shows a wide range as Temple goes from being a

vivacious tease to a Stockholm syndrome survivor. After her rape, Temple seems to succumb to Trigger’s will.

While it might be argued if she is willingly going away with Trigger, the fact

that she makes no effort to escape shows that the spark in Temple is gone.

Temple does

get out from under Trigger’s influence, but only by committing a murder she

will apparently not be tried for. Killing someone is something that the

pre-rape Temple wouldn’t have been capable of doing.

Hopkins began

making films in 1930, debuting in Fast and Loose. The following year, in Dr.

Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Hopkins played a prostitute, Ivy Pearson, and even though

her part was eventually cut down to five minutes of screen time, she still

received rave reviews. Her big break came in Ernst Lubitsch's Trouble in

Paradise (1932) in which she plays a beautiful and jealous pickpocket, Lily.

She is

somewhat known for her Pre-code films, like The Story of Temple Drake and

Design for Living (1933), her third and final film with Lubitsch directing. In

that film, she is supposedly engaged in a menage a trois with Fredric March and

Gary Cooper. Hopkins was approached about, but turned down, the role of Ellie

Andrews in It Happened One Night (1934).

An actress

known for her versatility, Hopkins would appear in Virginia City (1940) with

Errol Flynn, The Heiress (1949), The Children’s Hour (1961) and The Chase

(1966), in which she played Robert Redford’s mother. Her final film was Savage

Intruder (1970). She would die of a heart attack in 1972.

Jack La Rue

was a Broadway actor who was discovered by Howard Hawks. Brought to Hollywood

to play a gangster in Scarface (1932), a role he lost to George Raft, he was

similarly replaced by Humphrey Bogart in the film version of The Petrified

Forest (1936). A poor man’s Bogart, La Rue would never achieve the fame of the

actor he was sometimes confused for. He did have a long career appearing in A

Farewell to Arms (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Captains Courageous

(1937) and The Sea Hawk (1940). He was the narrator for the television versions

of Lights Out for 32 episodes in 1949-50. His last film was Paesano: A Voice in

the Night (1977).

La Rue’s

Trigger represents the dark side of the pseudo-Bogart persona he evokes. But Bogart

never played a character like Trigger. He may have played gangsters in many,

many films, he may have been a murderer, but he never portrayed a rapist. This

is a thankless role and La Rue does his best with it.

The other characters don’t carry as much

weight, so to speak, but two are worth noting. William Gargan, who portrays Stephen Benbow, had been in films

since 1929’s Lucky Boy and had appeared in Rain (1932) and would appear in

films throughout the 1930’s and 40’s. Later, Gargan would find some success on

television in the Martin Kane, Private Eye and The New Adventures of Martin Kane, which

ran for 39 episodes in 1957-58.

Sir Guy

Standing, who portrays Temple’s grandfather, Judge Drake, served in the Royal Naval

Volunteer Reserve throughout the First World War and reached the rank of Knight

Commander (KBE) in 1919. After becoming a stage actor in Britain and the US he

moved to Hollywood in 1933 under contract to Paramount Pictures. The Story of

Temple Drake was his first of about 18 films. His last role was in Bulldog

Drummond Escapes (1937). He would die from a heart attack after being bitten by

a rattlesnake while hiking in the Hollywood Hills.

As with the

book, rape is at the center of the controversy surrounding the film. While I

haven’t read Sanctuary, the rape in it is

supposedly depicted in much more brutal terms, committed with a corn cob.

Still, in the movie, Temple Drake’s rape, at the hands of Trigger, is portrayed

in some ways as her comeuppance for having wielded the promise of sex to get

what she wants from the boys in her life. That all works until she comes across

Trigger; he is not a boy, but a man who doesn’t take no for answer. He takes

what he wants.

His murder is

presented as Temple’s only means to escape his negative influence on her. With

Stephen complicity, she seems destined to escape punishment for the crime,

something else censors within and outside the industry would have problems

with. I’ve read reports that The Story of Temple Drake is responsible for the

enforcement of the 1930 Production Code, since the film proves that the studios

couldn’t be trusted to police themselves.

Fast paced, so

much of the action is not depicted, but is rather inferred. The audience has to

fill in the gaps the movie leaves, but it makes it easy to connect the dots. In

the end, the film is really more of a character study than a morality play. We

don’t see anything that wouldn’t appear on television today, granted on cable,

but there is nothing on the screen that most people would consider obscene by

today’s standards.

My interest in

the film is based on the fact the title is frequently mentioned when Pre-Code

films are discussed. I knew about its notoriety going in, which is one of the

reasons I wanted to watch it. I also knew not to expect a 1930s version of

something I’d see on Showtime or Netflix, but I was a little surprised at how

tame it really looked when all was said and done.

No comments:

Post a Comment